In Conversation With an Evacuee

‘I wouldn’t be the person I am today if I wasn’t evacuated during the war’

Growing up in the White City Estate in London, Doreen Simson had only ever known thick city smog and the hustle and bustle of the capital, until she took a train journey aged four that changed her life forever. Leaving London amidst the terrors of WW2, this train journey transformed Doreen from an innocent child into an evacuee overnight. As the 80th anniversary of VE Day approaches, I reflect with Doreen on her experiences growing up in the countryside with a family that took her in like their own, and regard her as a member of the family to this day. These figures were my own grandmother and my great grandmother, who after coming across a crying four-year old Doreen at the evacuee collection point, welcomed her into a life so different from the one she had in the city she had grown up in.

Dressed head to toe in purple, with her long hair piled upon her head, it comes as no surprise Doreen Simson is fondly regarded as the duchess by her close friends in the town of Crawley where she has resided since 1965. Simpson speaks in a thick cockney accent, addressing a love for fine bone china mugs, a preference that was birthed during her time as an evacuee. Aged four, Doreen was just one of the 800,000 children that was evacuated in 1941 when war broke out under operation ‘Pied Piper’ which saw the mass relocation of children to safer rural areas out of the city. The most transformative train journey of Doreen’s life, she specifically remembers her mother Nell telling her to not leave her brother Dennis’ side, as they were greeted with ‘children holding jam jars full of water for us to drink’ shortly after arriving on Welsh soil in the coastal town of Borth. This comfort was thrust away after her brother was picked prior to her shortly after arriving in the evacuee collection hall: ‘I remember crying so much. My mum had told me to stay with my brother and within minutes of ending up in this new place, he had gone. That’s when your great grandmother Jean Sharpe came along, and I became a member of the family. She took a look at me, saw me crying and said ‘I’ll take this one’.

Borth, with its coastal views and seaside air, was a place far from the White City Estate Doreen had grown up in: ‘Walks down country lanes with Mrs Sharpe were my favourite. Taking in all the wildlife, those walks have played a huge part in helping me become the woman I am today, especially when it came to my career as a florist. I was the first in my family to take up floristry, and this originated from my time spent in Borth with your family in the countryside’. Doreen’s family grew up working class, her mother a cleaner for the BBC, and her father a decorator: ‘My mother used to clean the VIP lounge at the BBC headquarters. We left Kensal Rise after I was born, making it hard to originally adapt to life in the countryside, despite it’s perks being away from the threats of war: ‘Whenever Mrs Sharpe would write letters to my mother, I would always sign at the bottom ‘I want to come home’ in my scrawly young handwriting. It took me a while to adapt to my new life’. When the time to leave came, Doreen doesn’t remember it being the expected song and dance you would think it to be after returning home four years older: ‘The train journey back is a blur to me. My brother greeted me at Paddington and the next thing I knew, I was being dragged down the stairs and into a house with a new baby. Some things had definitely changed during my time away’. Doreen chuckles to herself as she recounts the arrival of a new sibling in the house, yet notes that she didn’t find post-war London a place of great pomp and circumstance.

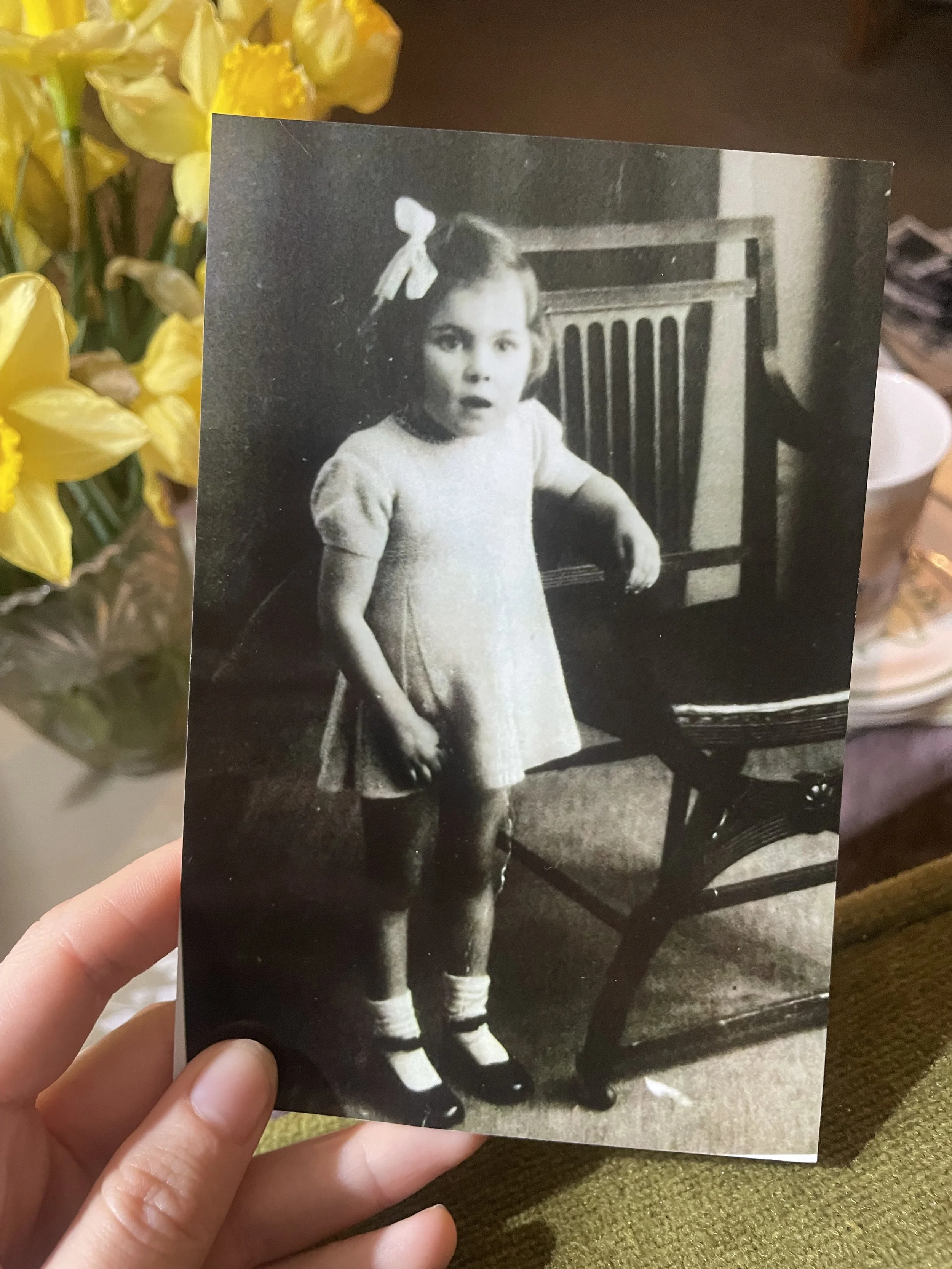

Image: Doreen as a child, aged four

Marked both by destruction and lingering relief, London was far from the city it had been before the war started. Looking around, widespread damage was everywhere you turned, and with resources in short supply, the road to recovery stretched far ahead: ‘I could see the damage on all the houses. We still didn’t have a lot to eat, and everyone knew that the next few months were going to be extremely different compared to the way we had been functioning over the past four years’. On the back of a foster family to miss, Doreen was newly-regarded as a snob in her family, refusing to swear, a pledge which she still maintains to this day, alongside a resolute aversion to a thick mug. Questioned on the bond between mother and foster parent, Nell and Jean never got the chance to meet, but Doreen knows how relieved her mother was for Doreen to be taken into a family that continued to extend their affection towards Doreen later in life, even joining them in the family car at the funeral procession of Jean Sharpe, the woman who took in a distraught four-year old Doreen at the collection point.

Many would find it hard to fathom today the sudden separation of parent and child, let alone the further separation of security through a sibling presence. Being so young at the time, Doreen repeatedly tells me she cannot remember the exact details of this experience, which I question if she thinks happens to be an after-effect from the traumas of war: ‘Potentially. I was just so young. I just know that I was so lucky to be taken in by your great grandma. My sister was one of the thousands of children that returned home due to mistreatment. Being a member of the evacuee association makes me realise my luck with the experiences I had across those four years’. Doreen’s voice takes a somber tone as she tells me about the commonalities of evacuee mistreatment, enduring physical and sexual abuse under foster families, scars which still remain to this day. Bed wetting in particular was regarded by some foster families as a symptom of neglect and poor mothering, yet speaking to Doreen, was a depiction of a child fraught with fear after being catapulted into the unknown and dramatically separated from their families overnight.

Image: Doreen as an evacuee in the Borth countryside (third from the left) alongside my grandma Mary Lynn, (first to the left) and my great aunt Heather (fourth to the right)

Reflecting on the 80th anniversary of VE Day, Doreen’s eyes gleam with excitement when I mention her Royal Albert Hall appearance- the question on everyone’s lips: Will the King make an appearance? ‘I’m a bit nervous but it will be such a cause for celebration. My friends here in Crawley often refer to me as their celebrity friend, and now being on television will help build their case against me even more. The celebrations, however, have come at a price, and I have such empathy towards any child today that is going through war. My experience is nowhere near as bad as the children you see on the television in war torn countries. I was extremely lucky to be welcomed into that house in Borth from day one, greeted by all the girls sitting around the table. There was a very strong female presence in that household’. Being an evacuee was not Doreen’s first and only obstacle in life, after marrying at age nineteen and giving birth to her only child Lee at 21, Doreen’s first husband was an alcoholic, prompting Doreen to eventually leave the marriage, and uphold her floristry business which saw her selling flowers all over London for twelve hours a day, from Shepherds Bush to Willesden Junction up until retirement aged sixty seven .

At the end of our conversation, Doreen reads a poem to me (the only one she says she has ever written), that truly captures the vulnerable fear of being evacuated. With descriptions of teddies under arms and the repeated phrase ‘They took us away on a train to a strange place’, it serves as an outpouring of childish uncertainty, uncomplicated in it’s messaging that no matter how many anniversaries reached, being evacuated aged four completely changes the course of your life forever.

Image: Doreen today